| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Older age

Higher eye pressure (even if it is in the normal range)

Family background (ethnicity)—more common in African descent

Having blood relatives with it

Being near-sighted (myopic)

Having lower blood pressure (but not high blood pressure)

Having conditions called exfoliation and pigment dispersion

Other than senior discounts, there are few advantages of getting older and one of the many disadvantages is a greater chance of glaucoma (of all types). While open angle glaucoma sometimes occurs early in life, by far most examples happen after age 60 and the number affected increases with older age. By age 90, nearly one in ten persons has it. Scientists have lots of suspicions about the many reasons older age would make glaucoma more likely, but it’s obvious that humans' systems are more likely to fail with every passing decade.

The higher the eye pressure, the greater the chance for open angle glaucoma. About half of cases occur in persons whose eye pressure without treatment is higher than the normal range. Their tendency to get glaucoma probably comes from abnormal outflow of the aqueous humor in the front of the eye. Since water can’t get out fast enough, pressure is not only higher than normal, but it fluctuates up and down more than in non-glaucoma persons. Both a higher average pressure and a pressure that varies more are factors known to contribute to open angle glaucoma. Millions of persons have eye pressure higher than normal and never develop open angle glaucoma. They are called ocular hypertensives and we discuss them in the section Why isn’t glaucoma either there or not there? - What makes you an open angle suspect? Many ocular hypertensive glaucoma suspects fortunately lack some of the other contributing risk factors for open angle glaucoma, or their eyes possess better defense mechanisms against the stress induced by elevated eye pressure. They stay suspects and never get glaucoma, but need to be monitored with regular, detailed testing to make sure they don’t cross over. Meanwhile, about half of those with open angle glaucoma never have eye pressure above normal. This situation was once called “low tension” or “normal tension” glaucoma (see section Why do people with a "normal" eye pressure still get glaucoma?). Probably their eye wall delivers more stress to the optic nerve head than other eyes at normal eye pressure. This causes death of ganglion cells at eye pressures that most persons have their whole lives without damage. Fortunately, lowering eye pressure is beneficial even in these normal pressure glaucoma patients.

When you have several known contributing risk factors for open angle glaucoma, the collection of factors can be more serious together than they would be individually. For example, among those with a tendency toward glaucoma, it is bad to have low blood pressure, especially at night (or whenever sleeping) and bad to have higher eye pressure—and doubly bad to have the two together. For blood to nourish the optic nerve head and retina, it has to get to the eye, and with low blood pressure coming in and higher eye pressure keeping the blood out, the perfusion pressure is too low. One has to have pretty low blood pressure (or very high eye pressure) to get into a danger zone here, but specialists now keep better track of both blood pressure and eye pressure along with the general doctors who care for open angle glaucoma patients. While low blood pressure, especially at night, may be harmful in glaucoma, we still recommend that high blood pressure be controlled as needed to protect your overall health. Care should be taken not to over treat high blood pressure in persons with glaucoma. If you are experiencing low blood pressure at night, get dizzy at night, or snore (have sleep apnea), you should consult your doctor, since controlling these factors can reduce the risk of glaucoma worsening.

The lower the eye pressure, the better for open angle glaucoma. Some things that make it lower are aerobic exercise, avoidance of corticosteroid medications (even inhaled or nose sprays with steroid), and avoidance of drinking many caffeine-containing drinks per day (see section How should you change your life?)

Where your family came from in the world also affects the chance for open angle glaucoma. We now recognize that there is no clear way to test the genes of a person and to properly label them as derived from Africa or Asia or Europe. What is often called “race” is a very complex set of features and the census bureau and scientists studying disease resort to asking someone to state what they call themselves—so-called self-described ethnicity. When you look at the whole population together, we are becoming more related to one another as the world’s communication, immigration, and intermarriage increase. Yet, interestingly, when we do a study of how many people have open angle glaucoma and we compare those who self-describe as African-derived (black) and European-derived (white), the rate of glaucoma is 3-4 times higher in the African-derived. The rate of open angle glaucoma is nearly identical for African-derived Baltimore City residents and villagers in central Tanzania in Africa. This seems to tell us that the tendency to open angle glaucoma is inherited in a way that doesn’t depend heavily on diet, environment, daily or cultural activities, since these things are so different between these two populations of African-derived people. These two groups must share some inherited genetic similarities. It develops at an earlier age and leads to vision loss and blindness more often. So, given this bad news, one approach would be to say we should ignore the problem and hope it doesn’t get us. While denying the problem is a human thing, it’s a losing strategy. The right answer is to follow the treatment program.

Some studies of Hispanic persons also suggest a higher rate of open angle glaucoma. While we must assume that this is a real worry for this group, the question is even muddier as to whether Hispanics are as homogenous in genetic inheritance terms as other ethnicities. After all, in some studies, people were included as Hispanic because of the language spoken, not their family derivation. We have a colleague who was born in Central America and speaks Spanish as his primary language; he would be Hispanic if studied in Mexico City, yet both his parents came from Central Europe, and if they hadn’t moved, he would be classed as European-derived in a study done in Austria. This issue is complicated, indeed!

Many diseases, including glaucoma and breast cancer, can occur more frequently in certain families. These unlucky families have an unusual version of a particular gene that is passed from parents to children and greatly increases the risk of getting the disease. Our genes contribute to open angle glaucoma and having a close family member affected increases the chance of getting it by 10 times. So, among European-derived adults over age 40, the rate of open angle glaucoma is 2 in 100. But your chance increases to 20 in 100 if your Mom or Dad, brother or sister, or your adult child had or has glaucoma. We often hear “but, no one in my family ever had glaucoma—so why do I have it if it’s inherited?” Even though some families have increased risk for glaucoma, people with no family history also get it. Genes aren’t the only reason people get glaucoma. Or, perhaps the reason “no one in the family had it” is that they were never examined, or they died prior to getting it, or they didn’t tell anyone else in the family that they had it (see section How can you help your family avoid glaucoma damage?)

Those with family members who have glaucoma still have a very good chance of NOT getting glaucoma (80%), but they should be examined regularly, because otherwise they won’t know that they have it until it has done serious damage. Routine eye exams can help to avoid unnecessary vision loss in family members who are at risk. On the other side of the coin, we frequently hear from patients that their Mom had glaucoma, only to find out when records of Mom’s care are produced that she had cataract, or used daily eye drops for another problem, like dry eyes. In one study, more than half of those who said that they have glaucoma, in fact did not have it—and this was a study of nurses! It is even more important to have regular eye exams for glaucoma if your family member not only had it, but lost vision from it. The tendency to have worse glaucoma is probably inherited, too. At this time, there are many known genes in our human DNA that have mistakes called mutations which increase the chance of various kinds of glaucoma. These make up only a small fraction of all those with glaucoma and at present there is not a good reason to do testing for gene defects as a method to screen for who is going to develop it.

In this section, we explain that people with near-sightedness (myopia) are more likely to get open angle glaucoma. Myopia means you need glasses to see well at distances like 20 feet, but see things held close to your face fairly well without glasses. Myopic eyes are more often longer and have thinner walls. Both features make the stress from any eye pressure worse in causing glaucoma damage. Having laser treatments to change the need for glasses doesn’t improve this risk, and those considering such refractive surgery (LASIK, PRK, SMILE, etc.) should have careful discussions with the surgeon before doing so for two reasons. First, some forms of refractive surgery use an instrument that raises the eye pressure very high for some minutes. This could theoretically be dangerous for the glaucoma patient. Second, performing these refractive procedures changes the measurement of the eye pressure, typically making it seem lower than it is. We can correct for this best by knowing what pressure was just before and just after the laser refractive procedure. The bottom line is that those who have worn glasses for myopia since their teens should have annual evaluations for glaucoma in adulthood.

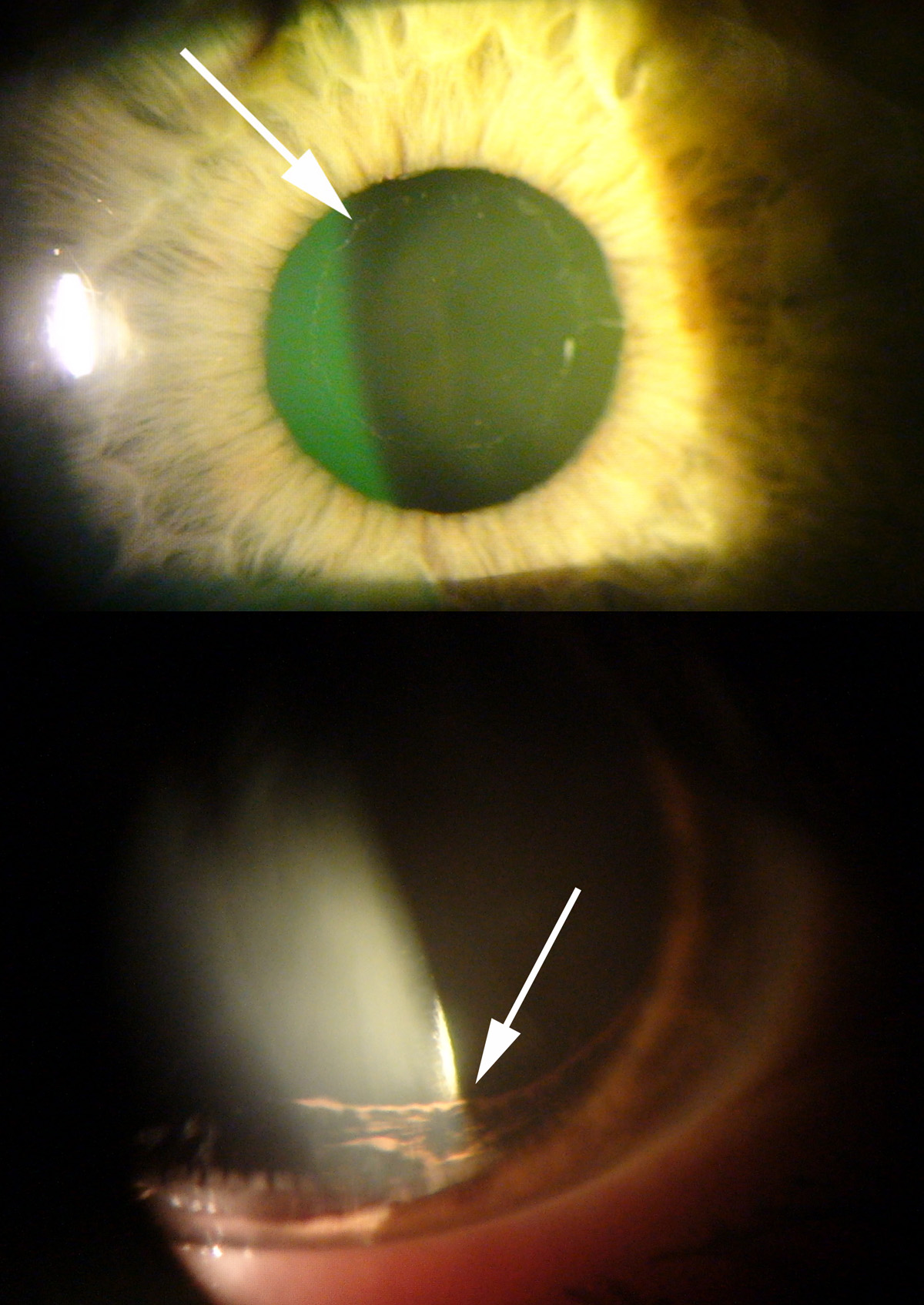

Two conditions that make open angle glaucoma more likely are exfoliation syndrome (also called pseudoexfoliation syndrome) and pigment dispersion syndrome (Figure 8). Exfoliation eyes produce a white dandruff-like material that can only be seen inside the front of the eye on the iris and lens. This material is produced by many cells in the body, but mostly causes trouble in the eye. Part of its damage comes from the exfoliation material blocking up the outflow of aqueous humor, so that the eye pressure is both higher and more variable than normal. Both higher pressure and more variable pressure are bad for eyes at risk for glaucoma. Second, there is some evidence that exfoliation eyes are more susceptible to glaucoma because either the structure of the eye or its blood vessels are weaker in exfoliation. We can see exfoliation in detailed eye exams in many persons who don’t yet show damage from glaucoma. They are best advised to have more frequent exams than others with less glaucoma risk.

The second internal eye condition that makes open angle glaucoma more likely is pigment dispersion syndrome, which happens in some myopic eyes. Their iris rubs on the structures just behind the iris, the supporting fibers that attach the lens to the eye. Pigment rubs off the back of the iris and blocks the outflow of aqueous humor when the pigment is carried to the trabecular meshwork. Eye doctors can see the places where pigment has rubbed off and the places it deposits on the inner eye, so before there is glaucoma damage it is possible to begin monitoring those with this condition more closely. While exfoliation is more commonly seen in the typical older glaucoma patient, pigment dispersion can begin to cause glaucoma in the 20s and 30s. The features that make pigment dispersion more likely are having a larger eye (being near-sighted) and having an iris that is less in its overall volume. At present, there is controversy about whether making a hole in the iris keeps the pigment from rubbing off in pigment dispersion. If it did, then laser iridotomy treatment would be helpful. A recent controlled clinical study found no benefit of iridotomy for pigment dispersion eyes. There is another kind of laser that works well for these kinds of glaucoma though and it is called laser trabeculoplasty. It will be discussed in the section on Laser glaucoma surgery: iridotomy and angle treatment.

|

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.