| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Take Home Points

The average patient only takes 70% of their drops—don’t be average

The chief problem is forgetting, and you don’t know you forgot

Using memory aids can dramatically improve drop taking

Link the drops to something else you do, keep them out in plain sight

Follow the 13 tips for taking drops

Your ability to put a drop on the eye every day means that you are in charge of keeping your vision with glaucoma. But, as we’ll see, the secrets of succeeding with drops are as much your head and your wallet as they are in how well you do with the mechanics of eye drop taking. In the next section, we’ll talk about the specific medicines now available as glaucoma drops (see section Glaucoma eye drops: choices, choices). Here, we’ll talk about how to get the drop in your eye and how to remember to do it.

The dirty little secret of glaucoma drops (until recently) was similar to what used to be a humorous description of the Soviet Russian economy, where salaries were low and no one really did much work. The joke by Soviet workers was: “I pretend to work and they pretend to pay me.” For glaucoma, it was: “I pretend that I take all my drops and the doctor acts like I take them all.” Twenty-five years ago, researchers put an early computer in an eye drop bottle and found that patients were taking only 3 out of 4 of their drops—even when the bottles were handed out free.

Studies done at our Wilmer Glaucoma Center of Excellence have confirmed that little has changed. What we know is very disturbing:

Of patients who are given a new prescription for glaucoma drops, 25% never fill the second one after getting their first bottle. They had not stopped because the doctor had switched them to another drop.

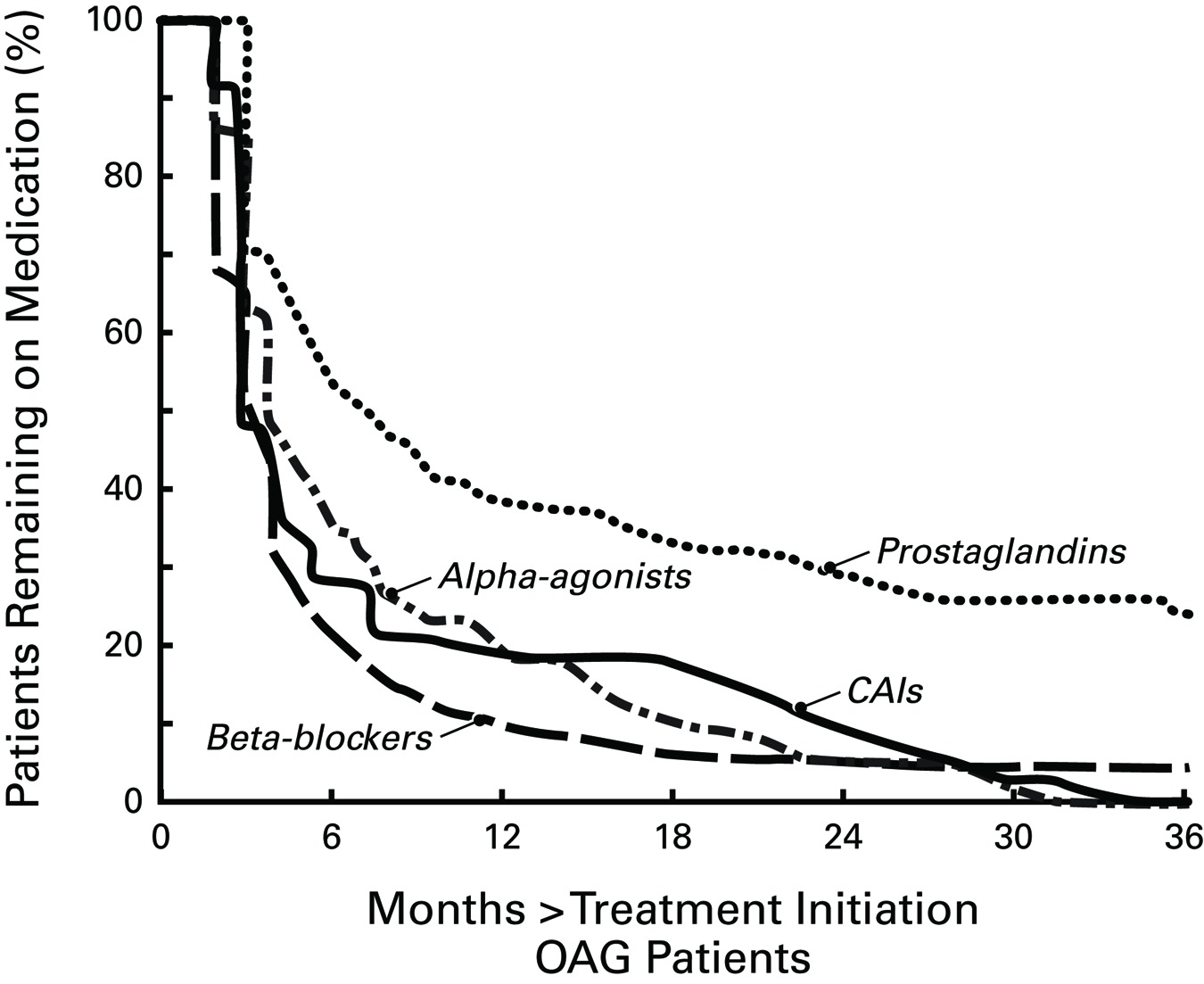

Of those who fill the second prescription, only half of all the patients are still taking their drops regularly at the end of the first year (Figure 20). This includes those who switched or went on to surgery or something else.

|

We gave our own patients free glaucoma drops and told them we were going to monitor how many drops they took using an electronic counter on their bottle that recorded when they took the drops. Even though we told them we were keeping track of when they took the drops and urged them to do their best to take them every day, the average patient took only 70% of the drops. Amazingly, when we interviewed these folks and asked how many drops they thought they were taking, they said they were taking 95% or more. We know and respect these patients and suspect that they believe that they are taking all the drops. So, it isn’t that they are lying to me. Most of them just don’t know that they missed the drops—that’s why we call it forgetting. Now with pills, if you have 31 pills to take in a month, when you get to the end of the month and there are 5 pills left, you know you screwed up. With eye drop bottles there’s no such clue. If you don’t have an iron-clad reminder system, you will forget.

While it isn’t an excuse, patients taking pills for long-term diseases that have no symptoms (like high blood pressure) do just as badly as glaucoma patients at remembering to take their meds. There’s only one kind of chronic medication that does far better than this, where patients take 100% of the pills on time. It’s the erectile dysfunction drugs (no surprise there).

Some of our patients took only 20% of the drops. These folks with big adherence problems have some characteristics we can identify. They may have serious memory issues, such as dementia. They may not understand that the drops must go in every day, which means there was a lack of appropriate education. They may have a personality that allows them to ignore that glaucoma can blind you. This is called denial. They do not have a family member with glaucoma. They aren’t as likely to have taken the time to find out about glaucoma. Cost may be a limiting factor for some. Sometimes people are physically unable to use drops because of an issue with their hands, like a hand contracture from arthritis. Another reason people skip drops is because their lives are so busy with other things that they forget! By reading this you’re marking yourself as someone who is more likely to win by taking drops better. Congratulations! But, if two or more of the statements above apply to you, you may have more trouble remembering drops than you think. Laser treatment or surgery may be a better option if you fall into this category.

Patients do best with drops right after the doctor visit, tail off between visits, then start using them better again during the week coming up to the visit. We all floss and brush our teeth like mad just before seeing the dentist, so this behavior is understandable though unfortunate. The secret to preventing vision loss is to be consistent and to take drops every day in between doctor visits. As we’ll see below, the key to making this happen is to use memory aids that are as strong every day as that just before going to see the doctor feeling.

One of the surprises of our studies was that we thought eye drop side effects were a big cause of not taking drops properly. We found just the opposite! Those who reported redness or stinging or blurring from drops were more likely to be taking them. We should have realized that if you’re not taking drops very often, you won’t have any side effects. Not that the side effects aren’t that bad—after all, those who reported some minor side effects from drops were taking 9 out of 10 drops dutifully.

So, how can we help patients do better with their drops? Our group has done two big studies that show that effective memory aids work very well. Those who were using only half of their drops improved dramatically after we helped them to do a better job. We tried several ways to remind them. First, we used an alarm that beeped when it was time for the drops. Second, we used telephone calls, emails, or text messages at the time that they were supposed to take the drop. These simple efforts helped patients succeed in controlling their glaucoma. There are also apps that can be downloaded on smart phones and tablets to help out.

There are some simple memory aids that you can use to help you take all the drops as prescribed. Inexpensive wrist watches and cell phone alarms can be set to have their alarm go off every day or every 12 hours. Partners and spouses can remind you to take drops. We call this acceptable nagging. A paper calendar sheet and a pencil can be set next to the drop bottle. Every time the drop is taken an X is put on the paper. By checking at the end of month, patients can see when they’re forgetting. An example is the patient who found that no drops were getting in every Wednesday night. Wednesday was bridge club night and she came home late and was missing the drops. Anything that changes your usual daily routine will be likely to cause you to forget your drops.

Memory aids to remember drops

Link drop time to something else you always do

Alarm clock, smart phone application, or wrist watch alarm set for eye drop time

Spouse or family member who reminds you every day

Paper calendar sheet and pencil to mark when drops are taken

Taking extra care to remember drops when away from home

Don’t hide the bottles in refrigerator or medicine cabinet

It also matters what time of day the drops are supposed to be used. Patients who plan to take drops every night at bedtime should not get into bed and start reading or watching T.V. before their drops go in, because they are likely to fall asleep and forget to take the drops. Make sure you take the drop whenever you do something you always do, like taking a morning pill, shaving, or putting the coffee pot on to brew. Out of sight, out of mind: don’t put drops in the refrigerator or the medicine cabinet. There are no glaucoma eye drops that need refrigeration of the bottle you are actively using (see section Glaucoma eye drops: choices, choices). They can be kept in room temperature conditions, but should not be left in an area where they can get hot. If the pharmacy or service sends you 3 bottles at a time, it’s fine to keep the ones you’re not using in the refrigerator, but not the one you have opened and are taking.

The doctor should be part of the solution (and our studies show that some doctors are part of the failure to achieve perfect drop taking). When we studied the behavior of eye doctors with their glaucoma patients, we found they could be grouped into 3 camps, which we called: skeptics, reactives, and idealists. The skeptics simply wrote the prescription for drops and acted as if it was up to the patient to take it. When their patients didn’t take drops well, they felt that there was nothing that could be done. The reactive group of doctors was willing to try to help patients with adherence with treatment when it was pretty obvious that there was trouble. The final group is one that we hope will be emulated by young doctors in training. These were the idealists—and actual data shows that their patients take their drops better.

Idealist doctors realize that taking medicine is a shared activity between doctor and patient. They establish a non-judgmental environment. For example, they discuss with patients how hard it is to remember to take every drop and agree that it is only human to forget sometimes. They ask questions in an open-ended way that lets patients talk about the problems that they’re having. They listen. The skeptic-type and reactive-type doctors in our studies did most of the talking during video-taped study of actual glaucoma visits. They asked closed questions like: “you’re taking your drops, right?” for which patients would have to be pretty bold to say “No”. Ideal doctors give patients a chance to tell them what they do and don’t know about glaucoma. We did a study in which we asked veteran glaucoma patients to tell us what the drops were intended to do. Unfortunately, there were some who didn’t understand that drops lower eye pressure and that lowering pressure stopped vision from getting worse. It is too often that we hear: “I’m taking the drops, doctor, but my vision doesn’t seem to be getting better”. That means we haven’t properly educated our patients on how glaucoma treatment stops further damage, but does not restore vision. Finally, ideal doctor behavior is to prescribe only the amount of drops needed, and to keep it as simple as possible.

It’s hard enough to remember to take the drops, but using the drops effectively requires more thought than most people realize. Information about drop-taking is unfortunately based on very little scientific data, and pharmacies and drug companies (despite what should be the case) don’t always help you to use the right amount of drug efficiently. If you sell a product by the bottle, then having someone use it up as fast as possible makes more money. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, capitalism is the worst form of economic system, except for all the others. We don’t have to feel sorry for drug companies and drug store chains—they’re making nice profits. But, if you ever had drops come pouring out of a bottle as soon as you began tipping it up toward your eye, you realize that the bottles aren’t designed to be easy to use (at least some aren’t).

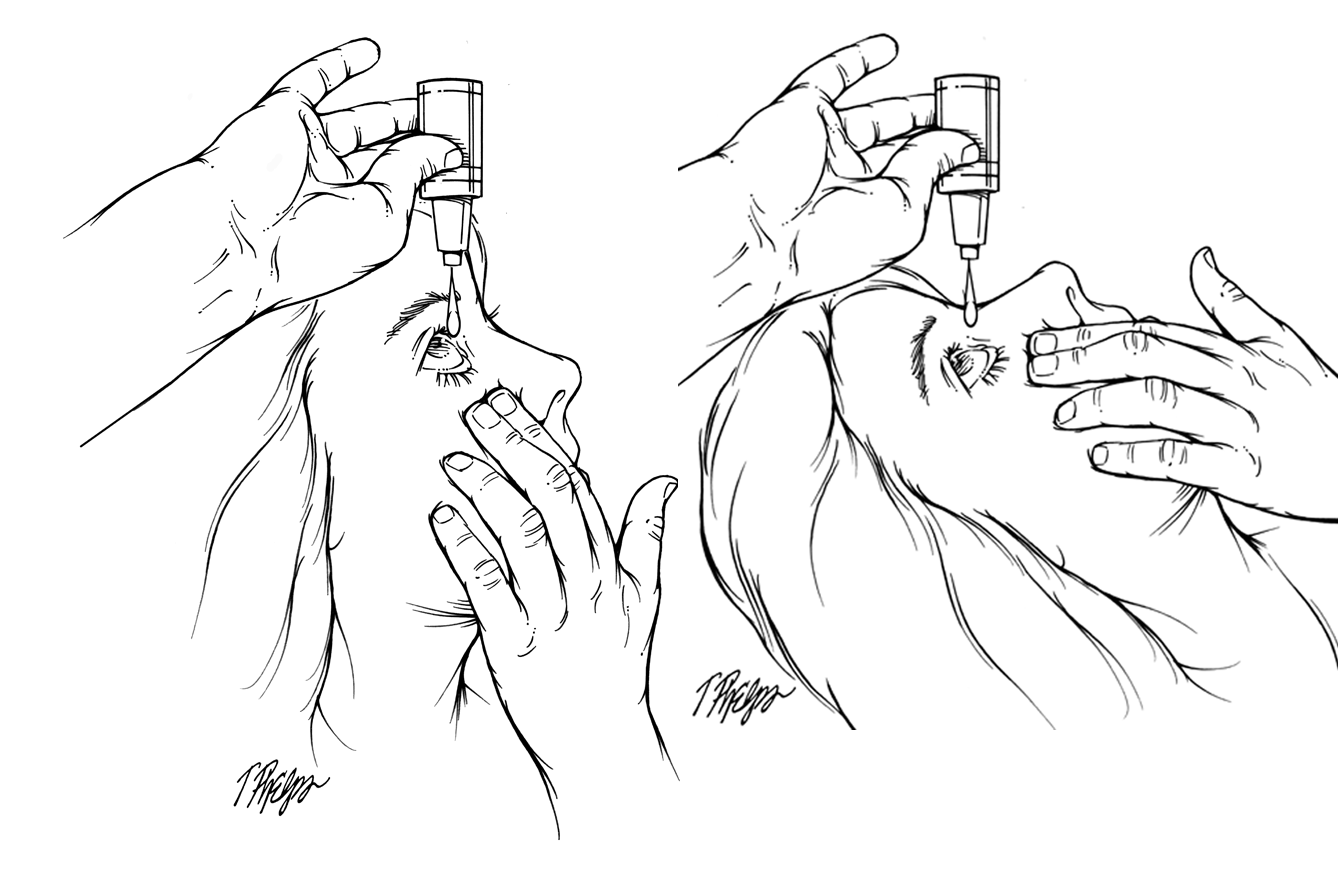

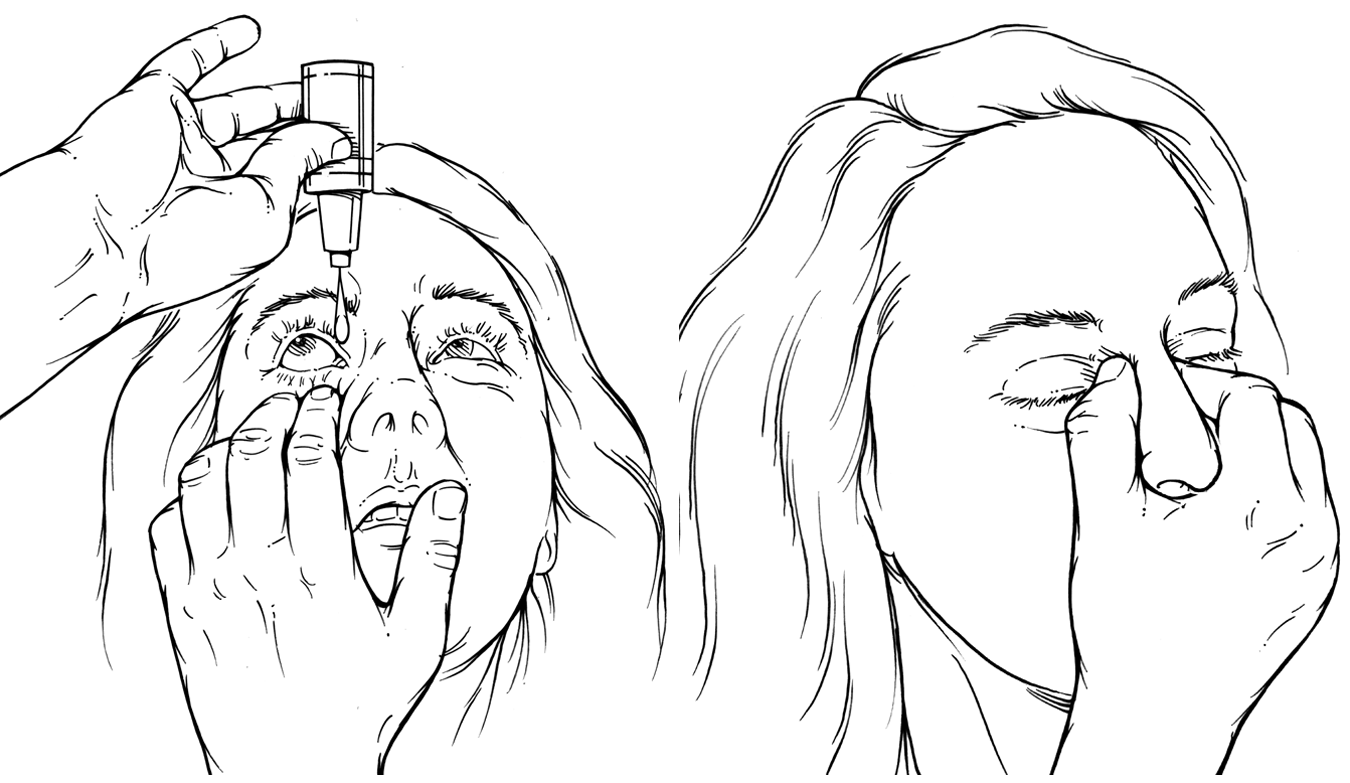

Here are the Lucky 13 ways you can get glaucoma eye drops into the eye and not on the floor, while being effective at lowering eye pressure (and saving money). See Figure 21 and Figure 22 for illustrations.

|

|

Face the ceiling when putting drops in. Maybe teenagers can look in a mirror, tilt their head way back and get a drop in the eye, but for most of us, several drops wind up on the floor that way. Get horizontal when taking drops, tilt your head way back while sitting in a big comfy chair or better, lie flat in bed.

Brace the back of the hand with the bottle on your forehead before tipping it up. We all have tremors and having the bottle waving around without support hurts your aim.

Next, before you tilt the bottle over, look up to see that the tip is over the nose half of your eye. Since you’re going to be looking through the top of your head (see below) when the drop falls, you can’t (and don’t want to) see it falling anyway. If any of the drop falls on the area on the nose side of the eye, even if some hits the edge of the eyelid or the inner corner, enough will get on the eye surface to do the job. If you miss on the temple side, it’s likely to treat the glaucoma in your ear, not your eye.

Pull down the lower eyelid of the eye with the hand that isn’t holding the bottle. This increases the target on the white part of the eye. As soon as the drop hits the eye, you can let go.

Let the bottle deliver as you tip it over and only squeeze if it doesn’t come out by itself. This means that you will tip the bottle over, above the nose side of the eye, and let it fall by gravity from about 2 inches or less. Some bottles start having drops come out right away. If the drop doesn’t come out by itself, squeeze gently until it does.

Use only one drop per eye! Yes, we know that some bottles say put in 2 drops (so does the information sheet from some drug stores). That’s a huge waste. Each drop (which has from 25-50 microliters of fluid) contains probably 5 times more drug than is needed for each treatment. So even if you have 80% of it go somewhere else than on the eye surface, you’re OK. The drop is absorbed mostly through the clear part of the eye, the cornea. Furthermore, using two drops gives you a greater chance for bad effects on the rest of the body. When you put medicine on the eye, it mixes with the tears, and this drains into the nose through the lacrimal (tear) system in the corner of the eye near the nose. That’s why you sometimes taste drops in your nose and throat when you take them. It’s also why cocaine abusers snort drug up their nose—it’s an effective method to get drugs into the body and head. The same goes for eye drops, but with drops you want the least amount anywhere else other than on the front of the eye.

As soon as you hit the eye with a drop, close the eyelids and don’t blink for 60 seconds. We’re now onto some pretty thin ice, scientifically. There is some evidence that not blinking leaves the drop on the eye longer—thus making it go into the eye more. But, when we tested the actual pressure lowering with and without the don’t blink instruction, it didn’t make a substantial difference. So it makes sense not to blink, but we can’t say it has definitive support.

Many doctors teach patients to push on the inner nose for 1 minute after putting the drop on the eye, to block the lacrimal drain area and keep drops out of the nose, throat and the rest of the body. Certainly, this naso-lacrimal occlusion makes logical sense, and there is evidence that for children this can reduce the level of drug that can be found in the blood stream after drops—which is a really good idea if you are someone sensitive to the general body effects of whichever drop you are using. However, very few patients are doing nasolacrimal occlusion correctly when we ask them to show us where they are pushing. The fingers must be far back from the bridge of the nose (almost poking the eye) and pushing almost hard enough to hurt in order to stop drug from going to the nose.

After the drop hits and you close your eyes, some will be on the skin of the eyelids. Blot off the excess, since some of us are sensitive to it or may have an actual allergy to the drug or its component parts. We don’t want to expose the skin daily to something that may lead to itching, redness, and puffy lids. This requires having facial tissues around before you start putting in drops.

You can treat one eye at a time, close, blot, push the nose, and then treat the other eye in the same way. Or, if you’re a veteran and can hit both eyes pretty quickly, you can do drop right, drop left and close both, blot both, and push on both sides of the inner nose with the thumb and forefinger for the 60 seconds. If you need to take more than one kind of drop at that time of day, it’s faster to do both eyes at once.

Wait between two types of drop on the same eye. Many glaucoma patients need to use more than one drug to keep pressure at target. They may have two or three bottles to put in, morning and evening. If you put in drop 1 and in less than 60 seconds you put in drop 2, the second one will wash away the first one and you’re not getting the full effect of either one. Now the controversy: how long to wait between bottles? We’ve heard doctors tell patients to wait 15 minutes! This would mean that the person with 3 kinds of drops would need nearly an hour to get the medicine in. There are no conclusive studies of how long to wait. We suggest that the shortest possible time should be 2 minutes, and if you have a system that lets you wait 5 minutes it’s possibly better. However, humans being humans, we know that if you put in drop 1, then say—"I’ll just dry the dishes and come back for the second drop," you’re more likely than not to forget to come back. Don’t walk away until they’re all in.

If you’re using more than one type of drop, the order in which they go in doesn’t matter. At least something is easy.

Running out of medicine can be a big cause of non-adherence. Many pharmacy plans give you either a 1 month or a 3 month supply of drug. They don’t usually give you more than you need and typically it is just barely enough if you use one drop at a time. The biggest cause of running out of drug is using too much each time. Use one drop if possible! A second cause for running out is not planning ahead. If you’re going to the beach, you won’t forget the beach chairs, but an astonishing number of people leave their eye drops at home. Most doctors can fill a new bottle at the ocean-side drug store, but you’ll probably pay full price for it. There is a third rule of drops, namely, they always run out late on Friday night after the doctor’s office is closed. Give things a shake on Thursday and see if you’re going to need more. Fourth, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) puts an “expiration date” on drop bottles. This is something to look for when the druggist gives you a 3 month supply—make sure they won’t already have expired before the 3 months is up. Finally, a very disturbing (but understandable) finding in one research project was that needing to use a second eye drop type every day led some patients to delay refilling the first bottle until they needed to get both bottles filled. Some drops come as combinations of two types in one bottle and this may help you with this problem.

13 tips for taking eye drops effectively

Face the ceiling

Brace the back of the hand with the bottle on your forehead

Look up to see that the tip is over the nose half of your eye

Pull down the lower eyelid

Let the bottle deliver by itself

Use only one drop per eye!

Don’t blink for 60 seconds

Push on the inner nose: nasolacrimal occlusion

Blot off the excess

You can treat one eye at a time

Wait between two types of drop

The order in which two drop types go in doesn’t matter

Running out can be a big cause of non-adherence

Some final aspects of drop taking. When asked to take them twice a day, patients ask if it has to be exactly 12 hours apart. Ideally, yes—but, practically, of course not. It’s good enough to hit it two times, one early in the day and one late in the evening. Time it to something you do at each time, and when you finish the morning dose, and will take the night dose at bedtime, move the bottle to where you’ll see it at night (and back after the night dose to where you do the morning dose, if that’s a different place). It is totally wrong, however, to take twice a day drops at 9 am and 10 am. Space it out as close to 12 hours apart as much as possible.

Some drops were approved by the FDA to be taken 3 times per day. In desperate circumstances, we have patients do this. They have to think up elaborate schemes for how they’re going to take the bottles along wherever they are and how to remember in the middle of a busy day to take them. Generally, we’d rather think of a different way to manage their glaucoma.

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.