| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Take home points for trabeculectomy

It works by producing a controlled leak of eye fluid outward

The area of surgery (bleb) is not usually visible except when you lift your eyelid

The target pressure is reached gradually by releasing stitches, painlessly

Success is achieved for years in the majority of patients

Problem areas are: too low eye pressure, late infection, and cataract

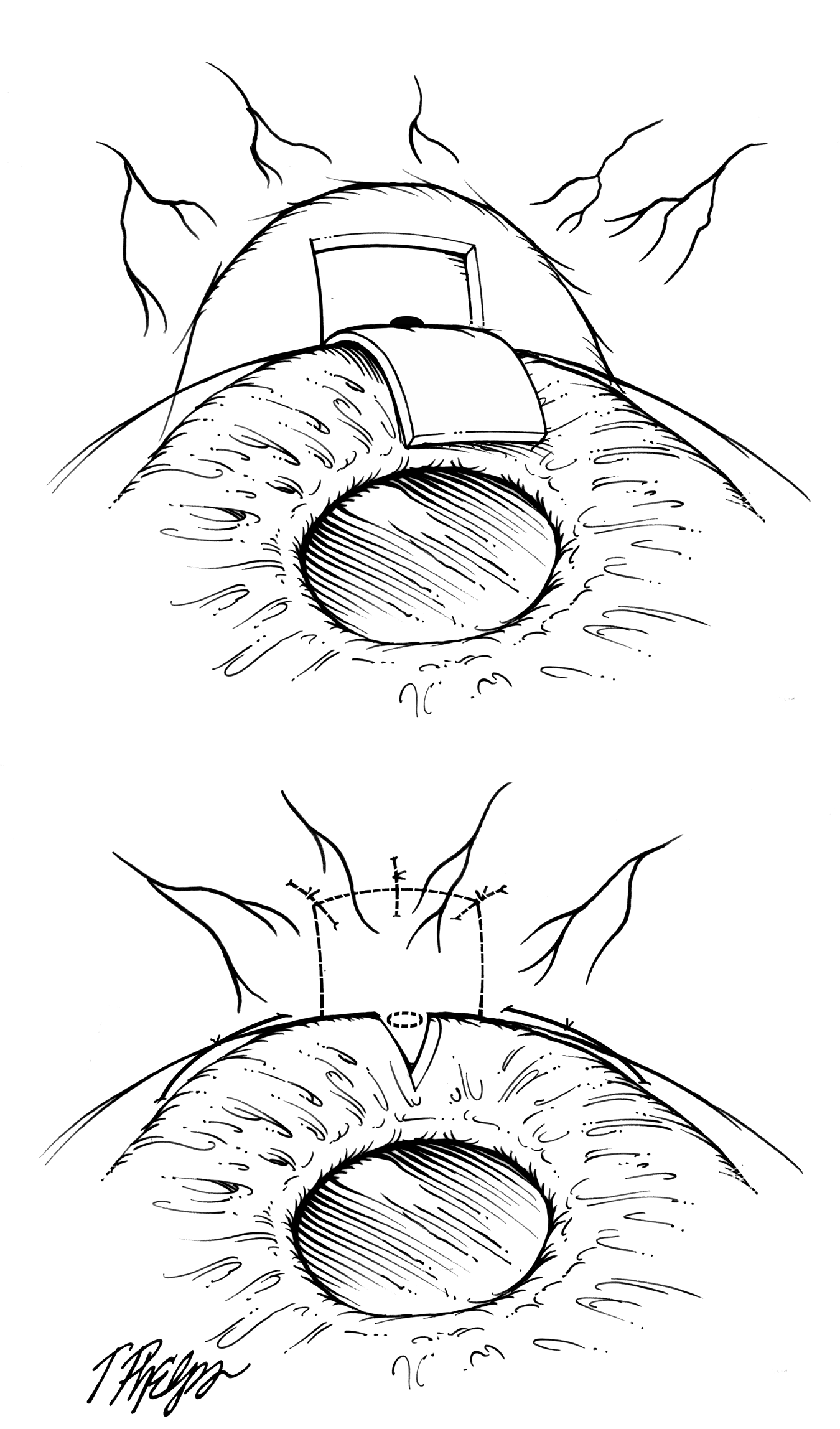

Trabeculectomy means removing a piece of the trabecular meshwork. It followed similar operations done since 1900. Their general purpose is to let water leak from inside the eye, out through the wall of the eye and under the covering tissue (conjunctiva) where it slowly leaks into the tears. Peter Watson of England developed the concept of the present surgery in the 1960s and improvements have been added about every 5 years since then. To summarize what is done (Figure 23), the eye has two layers near the junction of the white and colored part: these are the conjunctiva, a flexible tissue a lot like sandwich wrap, and the sclera, the strong white part of the eye. The surgeon cuts and folds back the conjunctiva, makes an apron-shaped flap half-way down within the sclera, folds the flap back and removes tissue enough to make a hole into the front chamber of the eye. The iris would plug up this hole from the inside, so a piece of iris is removed right under the hole. The flap is put back and sewn in place with tiny nylon sutures that act to keep all the aqueous from running out immediately. Therefore, trabeculectomy is essentially an adjustable valve. Then, the conjunctiva is sewn back in place to cover the area and to begin allowing aqueous to come through it slowly, like a sponge.

|

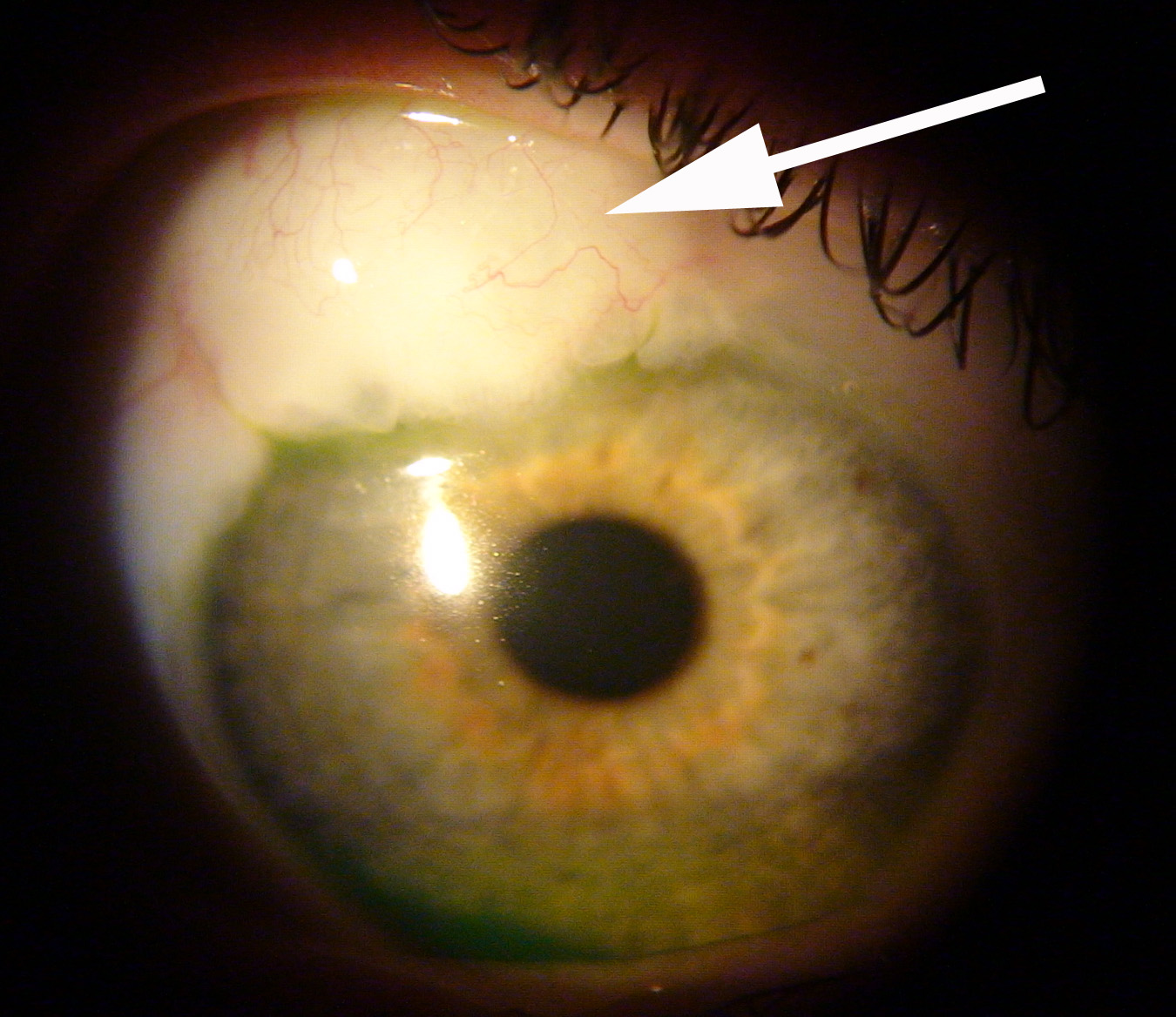

The area of trabeculectomy is always under the upper eyelid – there’s room up there for 2 of them if the first one doesn’t work long enough. Most often others can’t see where it was done, since it’s covered by the eyelid. The surgical area can be elevated somewhat by the fluid coming out. It usually has fewer blood vessels over it than the surrounding conjunctiva, so it looks whiter there. Eye surgeons call this the bleb, since it looks something like a bubble (Figure 24). We tell patients it will be there, but often they forget and six months later they are startled to raise their eyelid and notice the bleb. Mrs. Quigley calls this the "Saturday Morning I Just Noticed My Bleb" emergency call. It’s always good to be able to reassure someone that we call the bleb a success, not a problem.

|

The trabeculectomy works when more aqueous fluid gets out of the eye and the new pressure is at or below the target (see section What is the target eye pressure?). This means we have to fool the body into thinking it healed the opening shut when it didn’t. Several things help to do this. One is how the flap is constructed. Another is that the eye’s own aqueous fluid actually prevents healing, for the same reason that the iris doesn’t heal shut a laser iridotomy. Third, we often put a strong anti-healing medicine on the eye at the time of surgery to discourage the internal opening from closing—this is the drug mitomycin-C. Finally, you will be putting anti-inflammation eye drops on every few hours for a couple weeks and then slowly decreasing it, which is the final and important step in making the operation work by keeping the hole open.

Early after surgery, we want the pressure to stay a bit over the target. It helps to fool the eye into thinking nothing happened. So, on the one day, one week, and three week visits (there are about four visits all together), you may hear that the pressure is still higher than the target. We plan for that and lower it into the target range gradually. It is important that the pressure doesn’t drop too low too quickly. Remember that the flap of sclera was sewn with stitches—these can be released or melted to reduce their tension, so aqueous flows faster through the hole and the pressure falls. Some surgeons use releasable sutures that are removed during a standard eye exam without any pain. More commonly, they are released painlessly by a tiny laser delivery, one at a time.

We can tell a lot about how the operation is working during the first weeks. A few weeks or months after the operation, you’ll be stopping all eye drops to see if the target is achieved. We have patients whose trabeculectomy is still working 30 years later. Unfortunately, they all don’t work for three decades. About 20% of trabeculectomies fail to control pressure by one year. After that, about one in 25 (4%) stops working each year. In a review of trabeculectomies done at the Wilmer Glaucoma Center of Excellence, with lots of different patients, some with very difficult problems, nearly two-thirds were still at their target and on no medicine five years afterwards, and no further surgery had been needed for the eye.

The main problems that come up after trabeculectomy (other than a failure of the pressure to go down) are: too low a pressure early or later infection, discomfort caused by the bleb area, and bleeding inside the eye. Low pressure can cause blurred or variable vision, and this can happen both with a large hole in the bleb wall or without it. When pressure is very low, the layers of the eye wall can fail to stay in their normal position. They drift off into the eye, causing dark shadows that block vision. These are called choroidal detachments and, while they do not harm the eye permanently, they require treatment often to restore normal position. Another condition can occur when the pressure is low is called hypotony maculopathy. In this, the back of the eye becomes slightly folded (like a balloon losing air), blurring vision. While these are uncommon events, they can lead to permanent changes in vision. Dysfunctionally low pressure (hypotony) is fixed by removing the conjunctiva over the bleb, advancing the conjunctiva to cover the area, and restitching the flap back tightly. This is most often successful and in the vast majority, vision is improved and the target pressure is still achieved.

Any operation can have bacteria enter the eye during surgery. These are most often the patient’s own bacteria that normally live on the eye’s surface. We take steps to keep them out of the eye and to sterilize the eye surface just prior to and during surgery, but one in 1,000 or so operations have an infection develop in the first month. We let patients know the signs of infection that they should look for. When they call us promptly about such symptoms, we are very successful at treating infection without bad results. In an infection, the eye has pain, a big increase in redness, a sticky discharge on the lids (pus), and vision often is much worse. Any two or three of these should lead to a fast phone call to the doctor, even on Saturday night.

Late infection can happen with trabeculectomy and to a lesser extent with tube-shunt surgery even months to years after surgery. Why this is true makes sense if you visualize the operation: it’s a new channel through the eye wall from the inside chamber, then under the flap, and finally under the conjunctiva. If bacteria can get through the first layer of conjunctiva, they can swim or drift inside the eye much easier than in a normal eye, where the white sclera is intact. It’s obviously still hard for bacteria to get in, because among thousands of trabeculectomies, there are few infections. The rate is about one in one thousand operations each year after surgery. Again, one key to minimizing the risk of infection is to have patients recognize symptoms of infection and call in quickly. A bleb with an overt leak in the conjunctiva makes infection even easier.

For about a year after any surgery on any body part, the nerves in the area have to regrow and during that time things feel different. Most often this is minor and can be soothed by taking artificial tear drops (over the counter type). Many patients describe this as “it doesn’t quite feel like my old eye yet”. It is very uncommon for us to have to do surgery to fix these feelings, although occasionally the bleb gets too high or extends too far down all around the white of the eye and needs to be revised.

There are those for whom trabeculectomy works better and those in whom it’s unlikely to win. The success rate is higher in eyes without past surgery and in older persons. It’s like a senior discount: older persons heal worse, so the surgery works better. It's not so favorable if you scar a lot, have had other past eye surgery, or have ongoing inflammation in the eye or some form of secondary glaucoma.

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.