| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

The fourth test to diagnose glaucoma is the visual field test (also called perimetry). This test tells us if some vision, primarily mid-peripheral vision, has been lost. The test is done with an instrument that examines how each eye can see, looking one eye at a time. We cover the eye not being tested with a patch and put an exact lens correction in front of the tested eye to get the best results. The patient looks into a dimly lit bowl-shaped area (Figure 16) and small oval lights appear briefly in different places in the field of view. The hardest part for patients is to keep looking in the center of the bowl while responding that they see lights appearing in their side vision. The instrument records which lights you saw and didn’t see by when you press a button. Our natural instinct is to look over at where the target light appears. But, that would show what you see directly in front, where our best, center vision is (the fovea). Since glaucoma affects the mid-peripheral vision early on, we need patients to look at the center target throughout the test, so that we learn what damage may have happened in the area away from the center.

|

The second difficult part of field tests is how dim many of the lights are. We want to see how dim a light the person can see, so we must show lights that are hard to see. Furthermore, we have to test about 50 locations to map how well you see in this area. So, it isn’t just whether you saw any old light, but how well you did at the extreme limit of your ability. I often say this is like weightlifting. You can probably lift 5 pounds, but if I keep adding weight, at some point you won’t be able to lift any more. In a field test, that’s when things actually get started. The machine wants to know what you can just barely lift. When it gets to the point where you can’t budge it, the machine takes a few pounds off so you can do it, then adds it back until you can’t again. The process is called finding the threshold—where you can just barely see the light half of the time. Naturally, you’re going to think the test was hard. Just like the weightlifting test where I made you play around at your limit. In fact, during a field test the machine is trying to show you lights about 1/3 of the time that it knows you can’t see. So, you come away from the test thinking you’ve “failed.” People often say to us that they’re sure that they have bad glaucoma damage after a field test. When we look at their test, it is totally normal for their age—they think they failed because they couldn’t see every light, but that’s exactly how the test is supposed to work.

Talk to your doctor about the field testing and especially ask how well you did compared to others your age (that’s how it’s scaled or judged, like “on a curve”). The first thing the doctor wants to know is whether your test in each eye is normal or not. After the first test, each test is then compared to the prior ones to see if there is any worsening. Unfortunately, it doesn’t get better (at least not from present glaucoma treatment), although some people improve a bit just by having the test a second or third time—called the learning effect. Overall, our hope is that each patient stays as good as they were at the beginning of treatment.

We learned 20 years ago that field tests that take too long to do are simply giving poor information about the patient’s glaucoma. So, we have tried to speed up the test, getting it down to under 5 minutes per eye. There are even faster versions of the test for those with attention problems. Blinking normally is OK during a field test. If you find you need a rest, simply hold down on the response button to stop the test or ask the technician to pause the test.

To help us evaluate how you did on a field test, several “check trials” are done. One of these judges whether you were keeping the eye steady on the center target during the test. The technician can also see your eye on a T.V. monitor and may encourage you to look only straight ahead. Another check looks at whether you are responding when the target light isn’t being shown. Everyone wants to do well on the test, since that would indicate the least amount of glaucoma damage. Our desire to “win” sometimes makes us over-respond. Again, the technical staff or doctor will point this out during or after the test and ask you to be “surer” that the light appeared next time. There are other more sophisticated checks done as well.

The vast majority of persons can give good information on field tests. But, the first test or two often are not so good—it takes practice to know what to expect and to give reliable answers. So, doctors must do 2 or 3 field tests to get a real baseline idea of where you stand. The technician in the room during the field test is critical to helping you get a good test. The room should be quiet (no cell phones ringing) and the technician should be attentive to how you’re doing (and not going out for a break while you’re sweating blood looking at lights). Sometimes the technician will gently move your head to keep it centered or pressed forward in the right position.

|

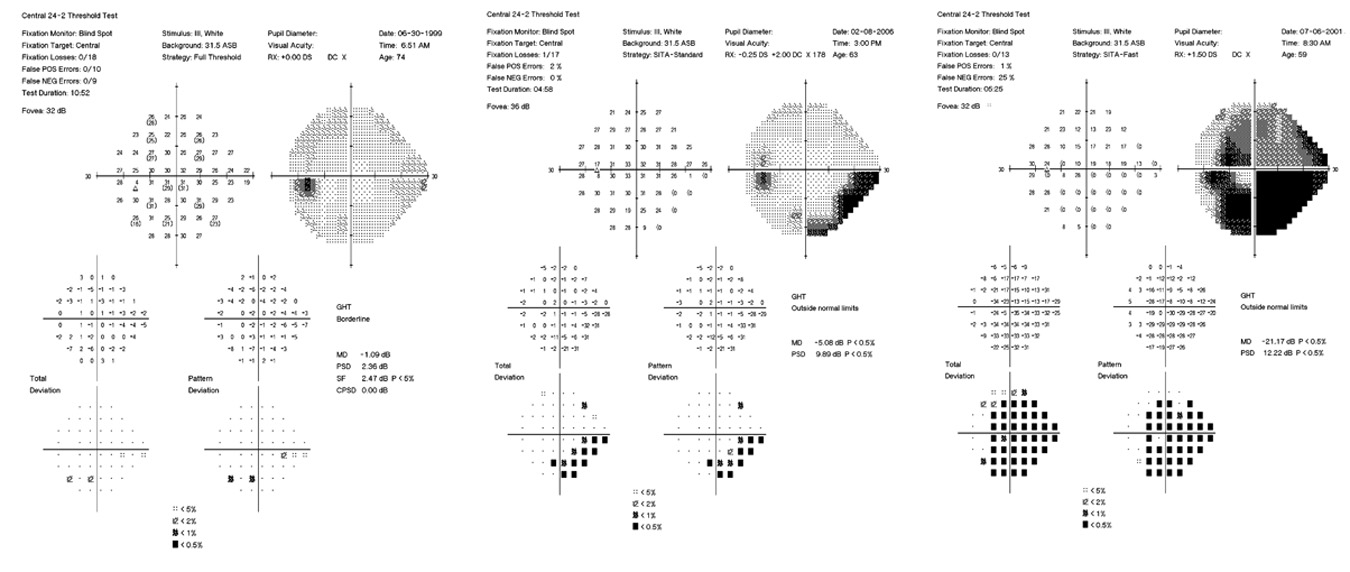

By comparing your answers to those of hundreds of normal persons who did the test before you, the machine comes up with the likelihood that each point is either normal or not. So, for each point across the whole field, we know how bad it is. Normal tests have no “black” areas, which are locations where vision isn’t normal. Initial glaucoma damage is seen as a cluster of points just above or just below the horizontal horizon, most often on the side toward the nose (left of center in a right eye). As the disease gets worse, more areas turn black and the field of view can contract down so that only the very center of the world is relatively normal, along with a separate island of sight way out to the side of the temple (to the right in a right eye). Amazingly, even at such a severely damaged point, persons will sometimes not have noticed the damage and are surprised and unbelieving when we show it to them.

For some reason, one eye is usually hurt worse than the other in the field (about twice as badly). Of course, this helps to maintain more normal function, since with one good eye we can do most activities of life without trouble. The average amount of worsening per year can be judged on the scale used for average damage, in units called decibels. The whole scale from normal to worst has 30 decibel units, and without treatment, the average person loses from 0.5 to 1 decibel unit per year after damage starts. With treatment, this is cut by more than half, so that over many years there can still be some loss, but not usually enough to be highly noticeable. The instruments now have software that shows graphs of how your fields are doing over time, and if things are getting worse faster than expected, this allows us to make a mutual decision to get more aggressive with therapy.

It would make sense that the fibers that are lost in the retina and optic nerve should have corresponding functional loss due to their absence. Because of the optics of the eye, the images on the retina are actually upside down compared to the real world, so when fibers that live in the upper retina and nerve head die, it causes loss of function in the lower part of the field test. In a perfect world, then, a glaucoma patient would have matching upper rim loss in the nerve head and lower field defects. When this happens, as it often does, the doctor can be confident that the finding is believable and should be taken as evidence for glaucoma damage. But, in a number of studies, persons who were moving from suspect glaucoma to established damage changed in their nerve head, but not the field, or vice versa. Both examinations have variability that explains why this might be true. Therefore, doctors should be doing both kinds of testing, structural (evaluation of the optic nerve and nerve fibers) and functional (tests of the visual field), so that nothing is missed. In general, the structural change happens first, and the functional (field test) second.

Take Home Points for Visual Field Testing

It tests how well we see at the side of vision (periphery) not in the direct center

You’re always going to think it’s difficult and that you failed to see all the lights

It often takes 2 or 3 tests to get good enough to give reliable answers (the machine knows)

Early damage happens on the nose side of the field of view, above or below the horizon

Progressive damage happens slowly enough it takes software to find it over several tests

Matching the optic nerve head and field damage is a good confirmation method

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.