| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

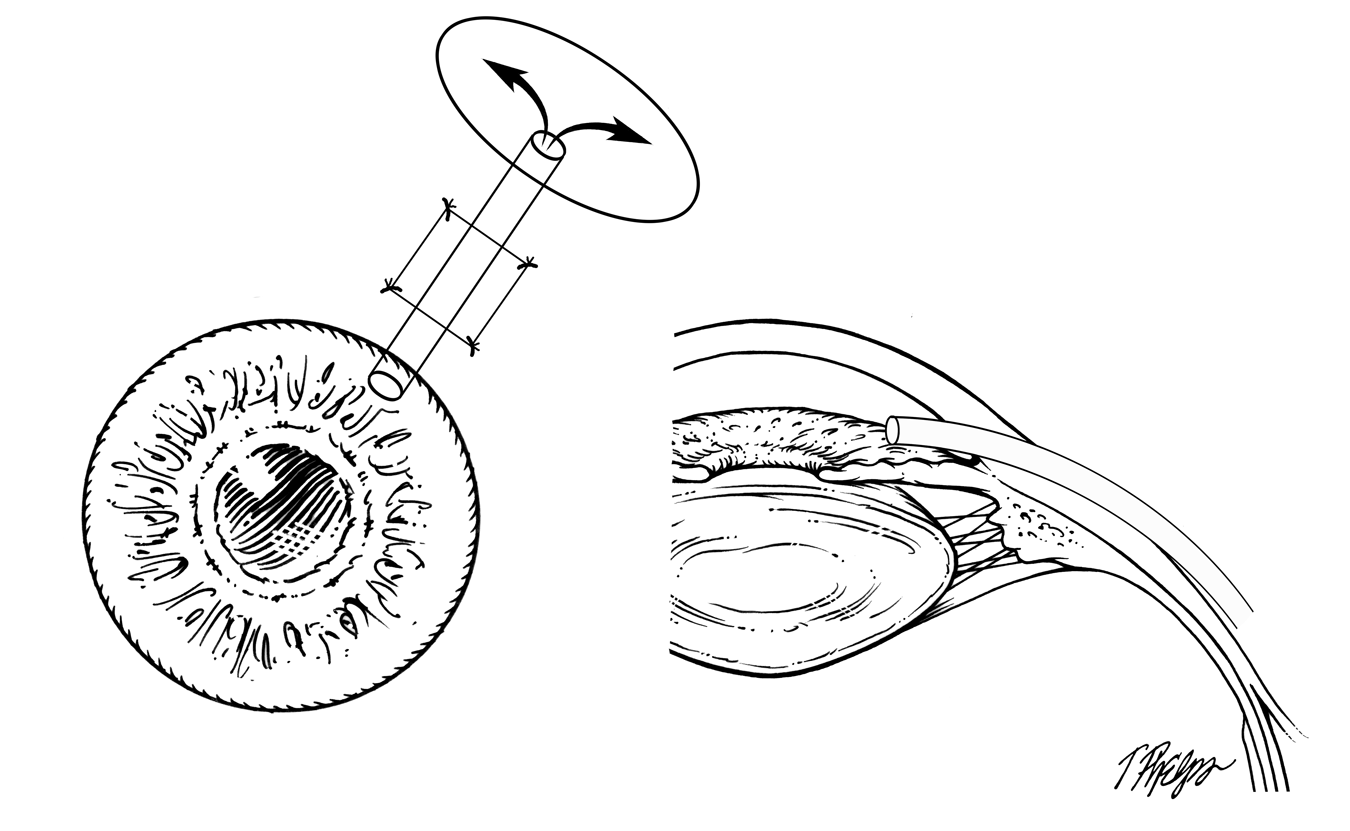

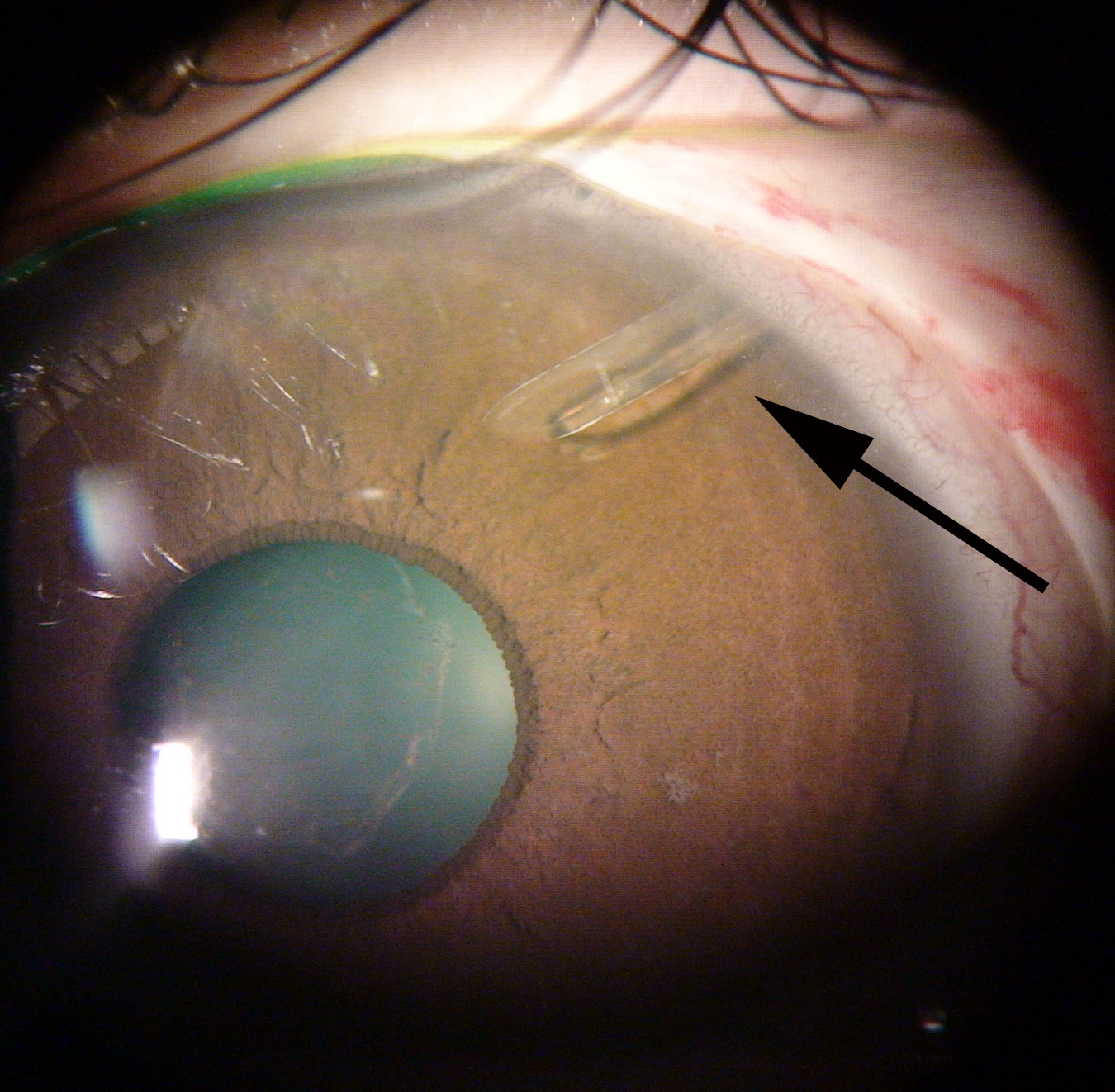

Tube-shunt surgery does the same thing as trabeculectomy: it lets aqueous humor out of the eye. It was designed to work when the normal area where fluid would drain out in a trabeculectomy has been scarred by prior surgery. However, recent randomized clinical trials show that tube shunt surgery is often a good choice as an alternative to trabeculectomy. The device that is implanted is a tiny tube of flexible plastic that goes into the front chamber of the eye and leads back to a flat area of artificial material that is sewn to the sclera of the eye far back where it isn’t seen (Figure 25). Fluid drains out of the eye, into the tube (Figure 26) and exits through in a large cavity that forms around the flat plate back behind the eye. Some brands of tube-shunts have a valve inside the tube that is intended to keep the pressure from going too low soon after surgery, while with others the surgeon temporarily blocks the tube off for about four to six weeks after surgery.

|

|

Materials that are sewn onto the eye tend to work their way out, that is, they can erode free to the surface, so the tube portion is covered by material from donated eye bank eyes that has been sterilized. The conjunctiva covers over the procedure and most often no sutures need removal.

Most of the pre- and post-operative experiences for trabeculectomy and tube-shunt surgery are similar. A recent study randomly compared tube-shunt surgery to trabeculectomy in eyes that had undergone prior surgery of some kind. In those eyes, the tube cases did as well or better than trabeculectomy in a number of areas, though each kept the pressure at or below target at about the same rate. The tube cases had fewer eyes that went too low in pressure, while the trabeculectomies needed fewer glaucoma eye drops in the short to medium term. Infections would be expected more often with trabeculectomy, but tube operations still can have the tube erode to the surface and may need recovering or removal. As many as one in ten eyes with tube-shunts have double vision for a time. This is because the materials sewn on prevent the eyes from moving together. It usually resolves with time, but in instances when it does not, we can prescribe glasses that will help.

Even more interesting are results of a randomized trial comparing trabeculectomy to tube-shunts in persons having their first glaucoma surgery. Again, both groups did very well, but for those persons who needed to achieve a target eye pressure below 15, trabeculectomy was significantly better, while tube-shunts were equally good for those starting with pressures in the 20s who needed only to be reduced to the high teens.

So, how do you decide what is better for you? In some eyes, trabeculectomy might be a poor first choice—for example, eyes with bad inflammation, eyes with secondary glaucoma that have new blood vessels growing, and some eyes of children with glaucoma (see sections Secondary glaucoma and Children and glaucoma). In addition, if someone needs to wear contact lenses to see best and can’t switch to eyeglasses, trabeculectomy with its bleb presents too great a risk of infection and the tube-shunt is a better option.

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.