| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Take Home Points

Glaucoma often has no symptoms

Nerve cells in the eye die slowly

Vision off to the side is affected first

Once vision is lost, it can't be regained

Glaucoma is related to eye pressure

Most likely, you were told you had or might have glaucoma at a routine exam of your eyes and had no idea that anything might be wrong. The most common types of glaucoma give no indication that they’re there (the medical term for this is that the disease is asymptomatic). There are two main types of glaucoma: open angle and angle closure glaucoma. Half of the people in the developed world with these types of glaucoma don’t know they have the disease, while in the developing world most cases are unfortunately undiagnosed and untreated. This is partly because some people don’t go for eye exams. It is also because not all eye doctors recognize glaucoma when they examine the eye.

When you look at something, the light enters your eyes and images of what you see are transmitted to your brain. Your eye has several major parts that do this job. Each of the parts is made up of cells, which are the building blocks of your body. These cells have different specialized jobs; some hold your body together like bricks and mortar, while others send messages to each other like a cell phone signal going through a tower to another cell phone. When light comes into the eye, the light is received first in nerve cells called rods and cones. These cells (also called photoreceptors, because they receive the light) send information about what you are seeing to a second layer of cells. Finally, the second layer of cells light up a third layer of cells, known as the retinal ganglion cells. The retinal ganglion cells send the message from the eye to the brain.

Retinal ganglion cells are the cells that die in glaucoma. Once they die, they are not replaced by new ones. This is not true in your skin or even on the front surface of the eye, the cornea, both of which make new cells all the time. Ganglion cells have their main body in the eye and a long fiber projects from them to the brain. There is a good reason why brain nerve cells don’t normally make new cells. New ones might disturb the functioning of the ones that are still working properly. We must think of how complex the brain is. There are 1 trillion nerve cells in the human brain, and each has about 100 connections or synapses to other nerve cells (100 trillion connections—100,000,000,000,000 for those who like zeroes). In addition, ganglion cells in the retina are surrounded by supporting neurons called amacrine cells and other supporting cells called glia. In the eye, there are 3 kinds of glia: astroglia, because they are shaped like pointy stars; microglia because they are small; and Müller cells because Dr. Müller got them named for himself. From the time the 3 nerve cell layers of the eye, called the retina, begins to develop in the womb, until around the time of birth, nerve cells are turning into the various types that will be present in the adult (about 10 kinds in the retina). Up until the age of 6, the eye’s nerve cells are still forming their final permanent connections to other nerve cells in the eye and to partner cells in the brain. Some eye nerve cells connect to other nerve cells at both ends, picking up information from a previous layer and passing it along to the next layer. The ganglion cells that die in glaucoma are that kind of double-ended neuron.

Even more amazing, ganglion cells pick up all the information from all the other nerve cells in the retina and carry it out of the eye on their one fiber through the optic nerve head (Figure 1) to the next way-station in the brain (the lateral geniculate). From there, there is another relay to the back of the brain where more complex visual processes go on. The ganglion cell’s fiber is amazingly long. If the cell body in the retina were the size of a basketball, the fiber would be as long as a football field (the actual fiber is about 2 inches long). On its way, this fiber has to pass through the wall of the eye to get into the brain. The optic nerve head, where the fiber leaves the eye is the ganglion cell’s Achilles heel, a spot where the stress of the eye wall and the need for good blood supply in a tight spot can kink it and lead to its death (see section How did you get glaucoma?).

|

|

Once a large number of ganglion cells die from glaucoma, a person may start to lose their peripheral vision. How many have to die to cause detectable vision loss? Glaucoma Center of Excellence research shows that it takes the loss of about 30% of the ganglion cells to reach the point where the doctor’s tests (visual field tests) show that a person’s vision is definitely abnormal.

Glaucoma creeps up on us without notice because of several features. First, it involves the slow loss of retinal ganglion cells (Figure 2). Because these cells carry the visual messages through which we see, losing them causes our vision loss. But, ganglion cells die so gradually that people affected by glaucoma don’t notice it until late in the disease. We begin life with around one million ganglion cells and barring major eye disease, 75% of them last until we are 90 years old.

The second reason glaucoma is a silent disease is that the ganglion cells most likely to die are those that provide us with our side vision. Only late in the disease does it attack our center vision, where we have our 20/20 reading ability. We don’t rely as much on our side vision as we do the center vision. When we are reading or watching TV or surfing the internet, our attention is focused on the object in front of us, not things off to one side. This means that the vision loss from glaucoma is not noticeable in its early stages. You can get a feeling for where the initial damage happens by looking at Figure 3. Close your left eye and hold this book (or computer) at a normal reading distance of about 14 inches. Look at the right page with your right eye, where the words are in bold print. The typical place for early glaucoma damage to cause you not to see is on the left page, where some of the print has been removed as an illustration. Since we normally pay most attention to what’s directly in front of us, most of us would not notice anything wrong if this part of the vision were missing.

|

A third reason that glaucoma’s damage is not noticed early on is that it typically affects only one eye at first. The other eye is still fully functional. Both eyes get similar information about the world, and the brain converts the two separate signals into a single picture. With both eyes open, as we view the world, any object is seen by both eyes and its image is sent to the brain by both. If the brain gets the image from either eye, we see it and we think nothing is missing. In fact, loss of the image from one eye does cause a loss of the ability to see things in three dimensions. This ability is called stereoscopic vision and helps us to tell how far away from us something is in space. So, we can lose a lot of vision from one eye, but if the other eye is unaffected by glaucoma, we don’t notice. Clinical research from our Glaucoma Center of Excellence shows that the typical person with glaucoma loses twice as much vision in the worse-affected eye compared to the better eye, but if left untreated, eventually both eyes become abnormal and this really decreases our ability to enjoy life.

Fourth, we’re pretty adaptable creatures, and we alter our behavior to take account of the damage, even without knowing it. When researchers evaluate how much glaucoma damage it takes to affect patient’s daily activities, they find that damage has to be pretty bad before it is recognized as a problem. Yet, when the actual functional capability is measured, in such things as reading, walking, and driving, it is clear that persons with significant glaucoma damage read more slowly, walk more carefully, bump into things more, and give up driving sooner than others. One fundamental fact is that vision lost from glaucoma does not come back and no present treatment can restore it. We will need to insert new nerve cells, to reconnect the new cells to the cells that are still there, and to make those connections work with the existing connections in the way that they did originally. While our laboratory, along with others, has taken the first steps in this process, it will be years before successful restoration of vision in a human eye is possible (see section Can glaucoma be cured? for more details).

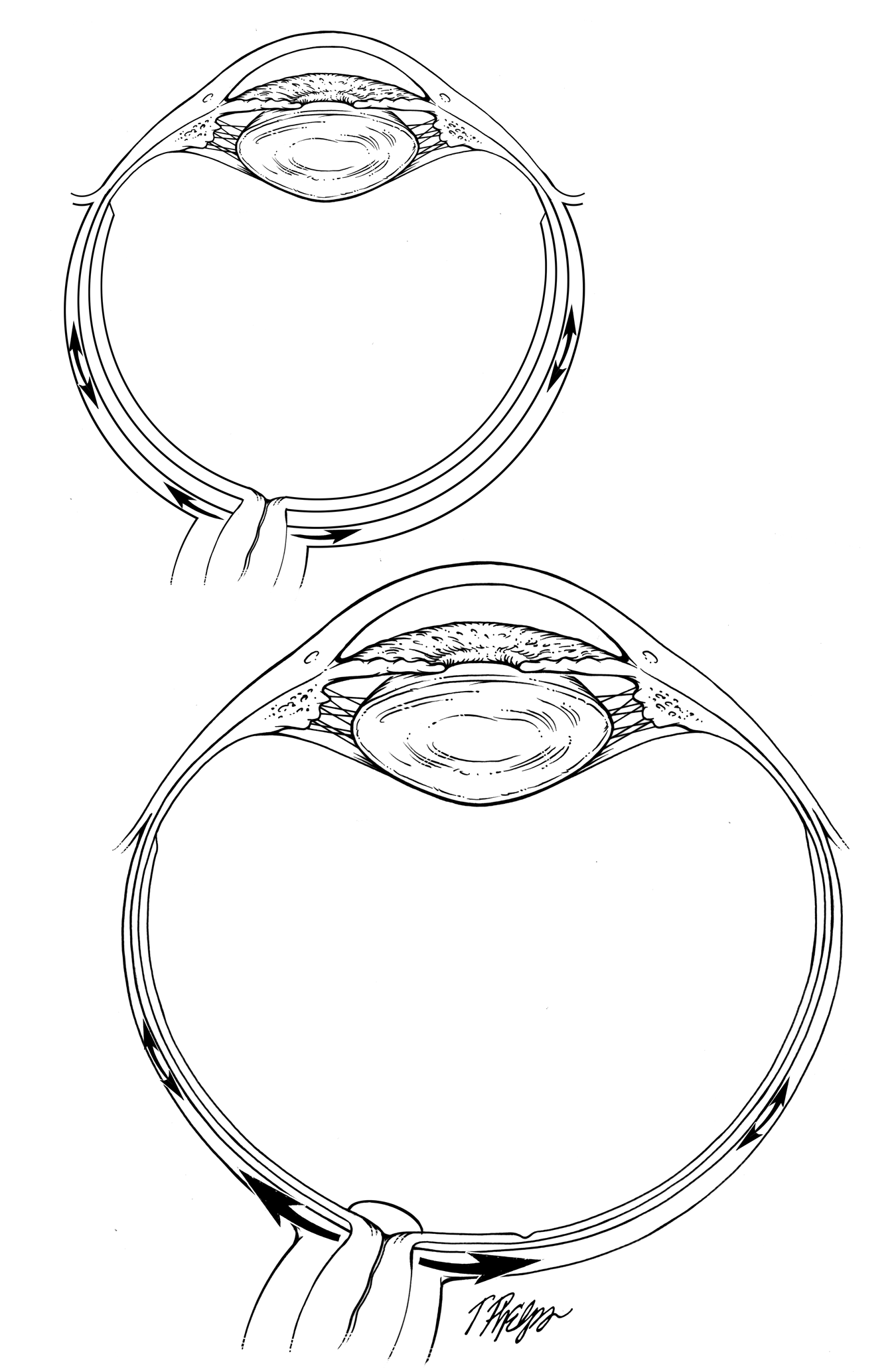

One final important fact is that all of the forms of glaucoma are related to some degree to the pressure inside the eye. The eye is like a camera, with lenses at the front (called the cornea and the crystalline lens) and the film or the digital receiving surface at the back (called the retina; Figure 1). For clear vision, we need the image to be placed on the retina and to not be moving, since if it is not stable, it would seem blurred. The eye is filled with fluid which must be kept within a narrow range of pressure (8 – 21 millimeters of mercury), like the air pressure inside of a bicycle tire. The fluid inside the eye is not the fluid we make when our eyes tear (or when we cry). Tears come from glands outside the eye and are not directly related to glaucoma. Like a bicycle tire, the eye must have the correct pressure inside to work properly. The balance between fluid flowing in and out of the eye maintains a higher pressure inside the eye than outside. This pressure difference produces stress in the wall of the eye (sclera), keeping it tense and stable so that the retina’s image is clear.

The normal eye pressure is about 15 millimeters of mercury. This is enough pressure to make the images stable on the retina by keeping the wall of the eye firm. The wall of the eye is made of 3 layers: the white outer layer or sclera, the middle layer containing blood vessels (the choroid), and the retina with its nerves. Pressure is maintained by having fluid come into the eye at one location (the ciliary body) and leave through outflow zones, especially the trabecular meshwork. The continuous flow of this fluid (the aqueous humor) also nourishes the structures inside the eye that have no blood supply of their own.

Whether the eye pressure is a bit lower or higher, there is always some physical tension (called stress by engineers) in the sclera. The higher the pressure, the more is the stress. Because the fibers of ganglion cells must go through the sclera at the optic nerve head to go up to the brain, they can be damaged by this stress (Figure 4).

|

Ganglion cells are damaged by prolonged eye wall stress, and this is the cause of damage to your vision in glaucoma. This means that the higher the pressure, the greater the chance for glaucoma. However, not everyone's eyes react to pressure in the same way. The fibers in some people's eyes can tolerate greater amounts of pressure than others. If my eye has a thinner wall than yours, or is bigger in diameter, it will have more stress from the same amount of pressure than does your eye (Figure 5).

Think of the eye as a water balloon filled to some pressure. If the balloon has a thick wall, it will be harder to get it to expand than if the wall is thin. In the eye, the balloon wall is the clear cornea and the white sclera. Certain rules of physics say that if two balloons are filled to the same pressure, but one is bigger than the other one, the stress in the balloon wall is larger in the bigger one. The reason the stress in the wall is important is that ganglion cells have to send their fiber out through an opening in the wall, the optic nerve head, to get their message to the brain. The fiber gets hurt by stress in the eye wall as it passes through. It’s like the canyon in the western movie, where the hero has to pass between narrow walls and the bad guys ambush him. In the eye, the fiber passes out with some tissue supporting the opening, called the lamina cribrosa (Figure 5). That structure is most like a colander that we use to drain spaghetti, the fibers of ganglion cells go out the holes and the struts around the holes try to resist the stress put on them by the wall of the eye pulling outward. The struts also have to resist the pressing from inside out, since the pressure inside the eye is higher than outside.

|

So, glaucoma can happen at any pressure, as long as the effects of stress are sufficient to kill ganglion cells. In fact, half of those with the most common type of glaucoma, called open angle glaucoma, always have a normal level of eye pressure. In their eyes, the stress of normal pressure (combined with other features) is enough to kill ganglion cells. Therefore, it is not necessarily “elevated” pressure that is the enemy in glaucoma, but any level of eye pressure can contribute to causing glaucoma in some persons (see section Why do people with a "normal" eye pressure still get glaucoma?). All present treatment for glaucoma is designed to reduce the damaging level of pressure, lowering it from its baseline to a safer level that will allow no further damage (see section What is the target eye pressure?).

Experts say that glaucoma has started as a definite disease in a person when one of the eyes has suffered actual structural and functional damage. This damage shows up as specific abnormalities on standard examination tests (see section What tests are needed to diagnose glaucoma?). There are many persons who are suspected to have glaucoma, but have not met the official damage criteria. They are called glaucoma suspects. Some eye doctors use the term glaucoma more broadly to mean anyone whom they intend to treat, whether glaucoma damage has started or not.

The next sections describe the various types of glaucoma and how they differ.

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.