| Glaucoma: What Every Patient Should Know |  |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Take Home Points

In narrow angle suspects, the iris blocks the view of half or more of the meshwork

Symptoms of past angle closure are an important sign

With signs of disease (angle scars, higher pressure, acute crisis), it’s angle closure, not suspect

With damage to nerve head and field test, it’s angle closure glaucoma

Which angle closure suspects should get laser iris hole (iridotomy) is controversial

All angle closure and angle closure glaucoma should have iridotomy

Behavior of iris and choroid are probably contributing features in angle closure

Plateau iris is a rare condition requiring additional treatment

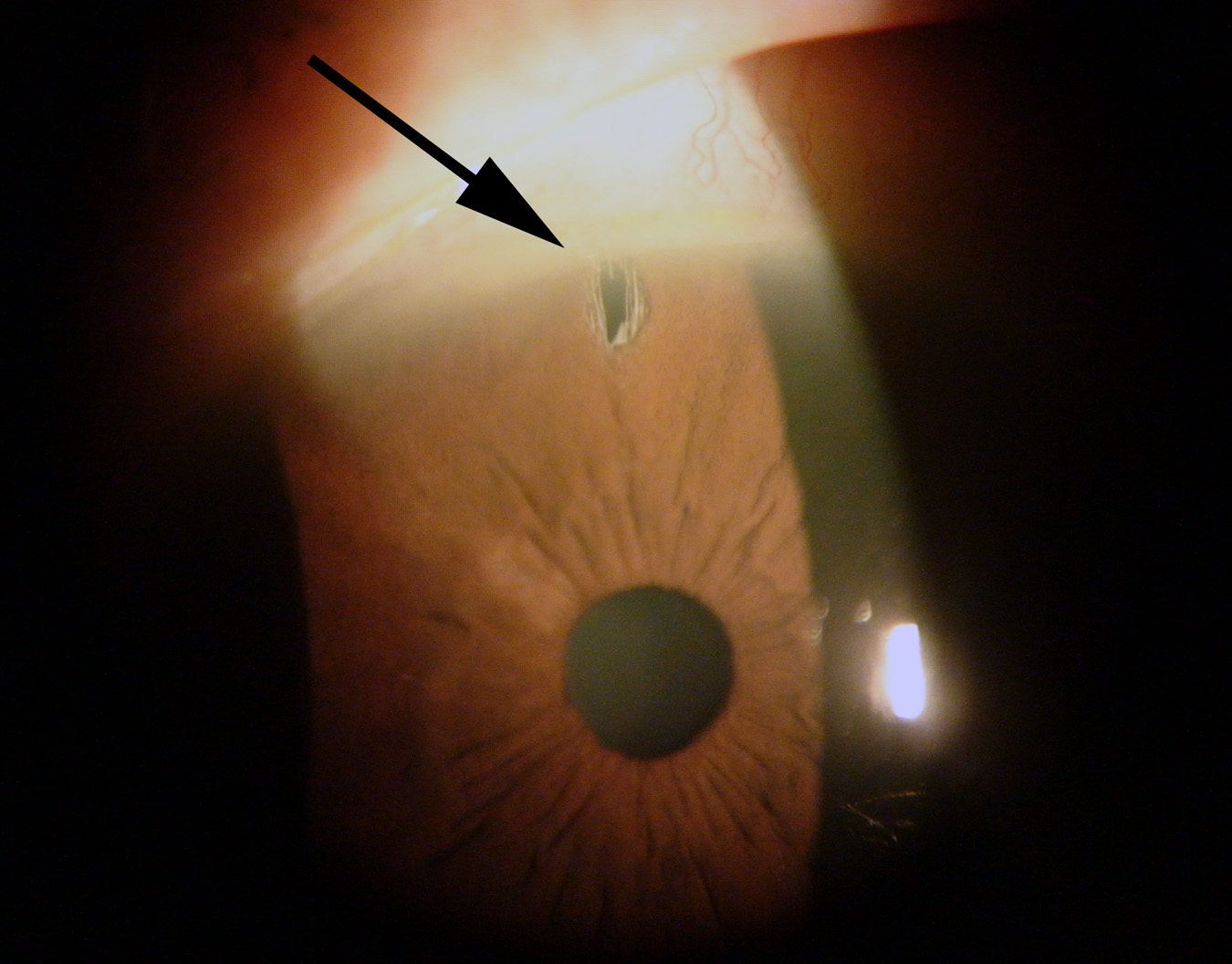

In the section How did you get glaucoma?, we listed some contributing factors for angle closure and angle closure glaucoma. These included older age, being female, being of Asian derivation, and having smaller eye length. However, the key to the new definition system mentioned in the preceding chapter (sometimes called the Foster et al or ISGEO classification) is the appearance of your eye by the gonioscope exam (see section What tests are needed to diagnose glaucoma?). Persons whose angles prevent a view of the trabecular meshwork through more than half of the angle in each eye are considered angle closure suspects. This means that the movement of aqueous from the back chamber of the eye to the front could potentially be blocked. Aqueous must come through the pupil opening and the lens is sitting right in the way in those who develop the actual disease. The way around the problem is to make a hole in the iris with a laser so the fluid is unblocked (Figure 18; for the actual technique description for the procedure, see section Laser glaucoma surgery: iridotomy and angle treatment). However, for every 100 persons with smaller eyes and narrow angles, only one or two will actually develop glaucoma. This means that small eyes and narrow angles are not the whole story and some other factors are contributing to the risk. Until recently, we didn’t know what these additional features might be. Doctors were forced into a tough dilemma. They could treat everyone with narrow angles (and do far too many laser iridotomies) or they could try to guess who might get the disease, and potentially miss treating the right one—putting that person at risk for missing out on a preventive treatment that is largely curative at a pre-disease stage of the problem.

|

Some eyes make the decision easier by showing that they don’t just have a narrow angle, but bad things have already started to happen from it. These persons have a condition called angle closure. They’ve gone beyond being angle closure suspects. One of the signs that angle closure has started to affect the eye is the presence of areas where the iris has stuck to the meshwork in the angle and can’t be pushed back during gonioscope exam (peripheral anterior synechiae). These happen by the following sequence (see Figure 7):

Narrow eye structures lead to a blockade of the aqueous moving between the iris and lens through the pupil

Pressure is higher behind the iris than in front of it, pushing the iris forward

The iris bows forward like a sail on a sailboat to touch the meshwork

The iris stays against the meshwork so long that it is permanently stuck there

The resistance to aqueous moving through from behind to in front of the iris is greatest when the pupil is neither big nor small—that is, when it is mid-dilated or about 5 millimeters in diameter. In the past, doctors tried to see if high eye pressure could be produced in suspect eyes by putting the patient in a dark room or dilating the pupil to 5 mm with drops—called provocative testing. Occasionally, these tests showed higher pressure, but recent research has pretty much shown that these tests don’t simulate how angle closure happens often enough to be useful. That doesn’t mean pupil dilation can’t sometimes lead to high eye pressure in a few suspect eyes. The reason that many pills, both over the counter and prescription, are marked as dangerous for those with “glaucoma” is their ability to dilate the pupil and make angle closure more likely (see section Can the treatments be worse than the disease?).

When the movement of aqueous through the pupil is blocked off and on, the iris bows forward to stop fluid leaving the meshwork, raising the eye pressure intermittently. If this happens over and over, eventually the whole meshwork can be damaged, whether it is actually studded with scars of iris to meshwork or not. As a result, higher than normal pressure is another feature that moves the suspect to angle closure status. Notice that this is an exception to the rule for open angle glaucoma about eye pressure. In open angle glaucoma, the pressure can be high or low and the disease might still be present. In angle closure and angle closure glaucoma, the reason for the disease is (by definition) that the iris is blocking the meshwork and the pressure rises. So, most often we find that angle closure eyes have higher than normal eye pressure, and in the angle closure group, having a higher than normal eye pressure is a sign that the angle appearance is likely blocking the flow of fluid out of the eye.

Finally, if there is total closure of the angle, then the eye pressure goes very high and an emergency situation has happened. This is an acute crisis (also called an attack) of angle closure (see section Acute angle closure crisis). Some eyes have had smaller, past attacks and the eye got out of it by itself. But, when this happens, there are tell-tale signs left behind for the doctor to see: areas of the iris get thinner and lose pigment, and the lens gets hazy areas. These are also reasons to consider that suspect status is over and real angle closure is present.

For all those with angle closure, especially those with the acute crisis, laser iridotomy should be done in both eyes. The evidence supporting this is very strong. Many years ago, when only the acute crisis eye was treated, attacks happened often in the other eye, and it was damaged needlessly. The approach of making a laser iridotomy in both eyes applies to all eyes with angle closure and to those angle closure patients who already have glaucoma damage (angle closure glaucoma). In angle closure glaucoma, it is very likely that further treatment will be needed with eye drops or even surgery after the laser iridotomy. One study even proposed that taking out the lens of the eye (cataract surgery), even when the lens was not cloudy, might be a reasonable early alternative to laser iridotomy to help those with pretty substantial angle closure glaucoma. People with angle closure and angle closure glaucoma should read the sections on eye drops and surgery, since they may be considering these therapies, too.

Why doesn’t iridotomy always cure the angle closure? As mentioned, the patient is typically not aware that the iris has been banging into the meshwork for months or years, causing damage to aqueous outflow. Laser iris holes stop further meshwork damage, and they almost completely prevent subsequent acute crisis, but they can’t reverse existing angle damage. The eye pressure is not only higher, but more unstable in persons with this kind of angle damage and the eye pressure will often need treatment to prevent further nerve head and visual field damage after iridotomy.

There is still controversy about which persons who are simply angle closure suspects should receive laser iris holes. The “treat everyone” approach suggests that making the laser hole completely stops most long-term problems from angle closure. Laser iridotomy is an outpatient, generally comfortable procedure to go through. The eye is numbed with drops for the procedure, and you will feel some pressure as it is being performed. It has few side effects or long-term bad consequences. Immediately following the laser, most people say their eye feels a bit light sensitive and uncomfortable. The good news is that the patient no longer has to worry that they will suddenly develop an acute crisis while on a cruise or trekking in Nepal. The alternative is the “treat very few” approach. Those who follow this philosophy argue that treating every angle closure suspect means the vast majority of treated persons are having laser treatment that is not needed—they may never develop the disease. The location of the laser iridotomy (the clock hour position) may influence the small chance of post-treatment symptoms, such as a glare-like sensation, which happens less than 5% of the time. Talk to your doctor about the planned iridotomy site before you undergo the procedure.

Once again, a person who is an angle closure suspect needs to be included in the decision. Some persons would worry every day that they were going to have an attack. We have met patients who carried around bottles of medicine in their purse to treat an acute attack in case it happened. For these persons, laser iridotomy is a good choice, especially if they have multiple risk factors (a family member with definite angle closure, a person with intermittent eye pains, or those with two risk factors, such as an Asian female with narrow angles).

For persons who are more bothered by the thought of having a potentially needless laser surgery on the eyes, we hold off doing the iridotomy immediately and examine them twice a year. Each exam includes gonioscopy to see if new scars have appeared in the angle, along with eye pressure measurement, as well as annual ophthalmoscopy and visual field tests. We have followed many persons in this way for the rest of their lives, without their developing any problem. If we didn’t treat any angle closure suspects, we would guess right over 9 times out of 10. Occasionally, one of the suspects who is being followed without treatment shows signs that angle closure has started (higher eye pressure, new angle scar), and then laser iridotomy is clearly appropriate. Rarely, an untreated person could develop an acute angle closure crisis. The risk of this is certainly very low. However, when an attack does occur, it is quite painful and must be treated immediately. One must discuss the risks and benefits with their eye doctor.

Research is actively being pursued at the Glaucoma Center of Excellence to determine better which of the angle closure suspects will develop a disease and need iridotomy early on. Part of our approach is to stop just measuring how small and how narrow the eye’s structures are, and to challenge the eye by seeing how it performs when conditions are changed. We have moved from measuring anatomy to measuring physiology, looking at dynamic behavior. An important part of being able to do this is the development of new imaging instruments to look at the front of the eye. For 20 years, the test called ultrasonic biomicroscopy (UBM) added much new information about angle closure. But, it was limited in its view of the eye and not too convenient for looking at dynamically changing aspects of the iris and angle.

We worked with a company to test the anterior segment optical coherence tomography instrument (AS-OCT). This allowed us to see how the structures inside the eye changed from moment to moment in eyes in their normal state, in an exam that is totally comfortable for the patient. Our dynamic approach is better than anatomic static measurement because it is like testing how fast a baseball pitcher can throw instead of measuring how big his arm muscle is. Dynamic measurements of the iris showed an amazing fact that had never been known in all the centuries that we’ve gazed at each other’s eyes. As light falls on the eye, the iris muscles constrict to make the pupil small (otherwise, we’d be blinded by the light). In the dark, we want a big pupil to let more light in (to see those navy blue trousers in a dark closet). The new AS-OCT machine can measure the thickness and area of the iris in the doctor’s office with no anesthesia. It soon showed that the iris is like a sponge: it sucks up water in the eye when the pupil is small and squishes the water back out when the pupil dilates. If it didn’t, the iris would be so fat that it might block up outflow of water in many eyes. When we measured the gain and loss of water from the iris in angle closure eyes, they failed to lose water when the pupil was big. Given that they have narrow channels for water to get out in the first place, this doubles their problem and is a contributing risk factor. A French research team has confirmed that angle closure patients who had an acute angle closure crisis were much more likely to have this feature of poor iris sponginess. Tests of iris volume loss are now being used in a number of advanced Centers to tell which persons should have an iridotomy and which should not. These tests will take several years of following persons before they have definitive results, but even now the data help us to inform patients better.

Just as the normal iris acts like a sponge and can have poor sponginess that contributes to angle closure glaucoma, the layer of the eye called the choroid can be a contributor as well. The choroid is the middle of 3 layers in the eye wall, between the retina (innermost wall) and sclera (outermost wall). It provides nutrition to the retina through its many blood vessels. It is typically only one-fourth of a millimeter thick. Optical coherence tomography technology allows us to measure the choroid’s thickness in living eyes without any pain or discomfort to the patient. We found that the choroid's thickness changes from moment to moment. The key point is if the choroid gets thicker, bad things can happen to the eye, especially to eyes with potential angle closure. If a hole hasn’t been made in the iris, thickening of the choroid can make angle closure more likely to happen. In some angle closure eyes, when the choroid thickens, it can produce a very difficult to treat glaucoma called malignant glaucoma. Or, when a surgeon is operating on an angle closure eye, choroidal expansion (thickening) can make the surgery much harder. There is now good evidence that many eyes with angle closure have choroidal expansion as part of the reason that they develop the disease.

A small number of eyes with angle closure have a condition known as plateau iris, in which the iris looks flat as it comes up to the angle by gonioscopy. After we do iridotomy, the majority of eyes with angle closure have a more open angle appearance afterward. About one-third, however, don’t look more open. Despite this, nearly all these “still narrow looking” angles don’t close, don’t lead into long-term angle closure or angle closure glaucoma, and they never have acute angle closure crisis. In fact, we make it a point to try to provoke attacks after iridotomy by dilating the pupil in every eye after iridotomy to show as best we can that the eye is safe from further high pressure. Rarely, when we dilate the pupil after iridotomy, the very high eye pressure happens again. This is called plateau iris syndrome and out of thousands of patients we’ve seen over the years, we can count on one hand the number of them with this syndrome. Most eyes with the plateau configuration won’t be at any risk for later acute crisis. But, when this unusual plateau syndrome does occur, we change the position of the outer iris by a different laser treatment called iridoplasty. These plateau syndrome patients are also sometimes treated with eyedrops to keep the pupil small most of the time (pilocarpine), and occasionally, cataract removal surgery or glaucoma surgery is needed (trabeculectomy or endocyclophotocoagulation).

If you would like to support the cost of providing and maintaining this book with a charitable donation of any size, please click here.